Nour Osseiran

Independent curator

ABOUT

I’m an independent researcher, curator, and volunteer paramedic based in Lebanon. My curatorial interest positions contemporary art, cultural history, and critical social issues at the intersection of social practice and activism. I am particularly interested in curatorial methodologies that challenge institutional frameworks and create more accessible and inclusive platforms for artistic expression. With a background in art history, my projects explore the political relevance of curatorial practice in contested public spheres through exhibitions, artistic commissions, publications, and collaborative initiatives that center conversation as a critical form of knowledge production and arts-making. My work is increasingly attentive to notions of fragility—of bodies, infrastructures, and narratives—and how curatorial practice can hold space for vulnerability as both a subject and a method.

CONTACT

Beirut, Lebanon

Recent Projects

Public Health

2025 | Lebanon

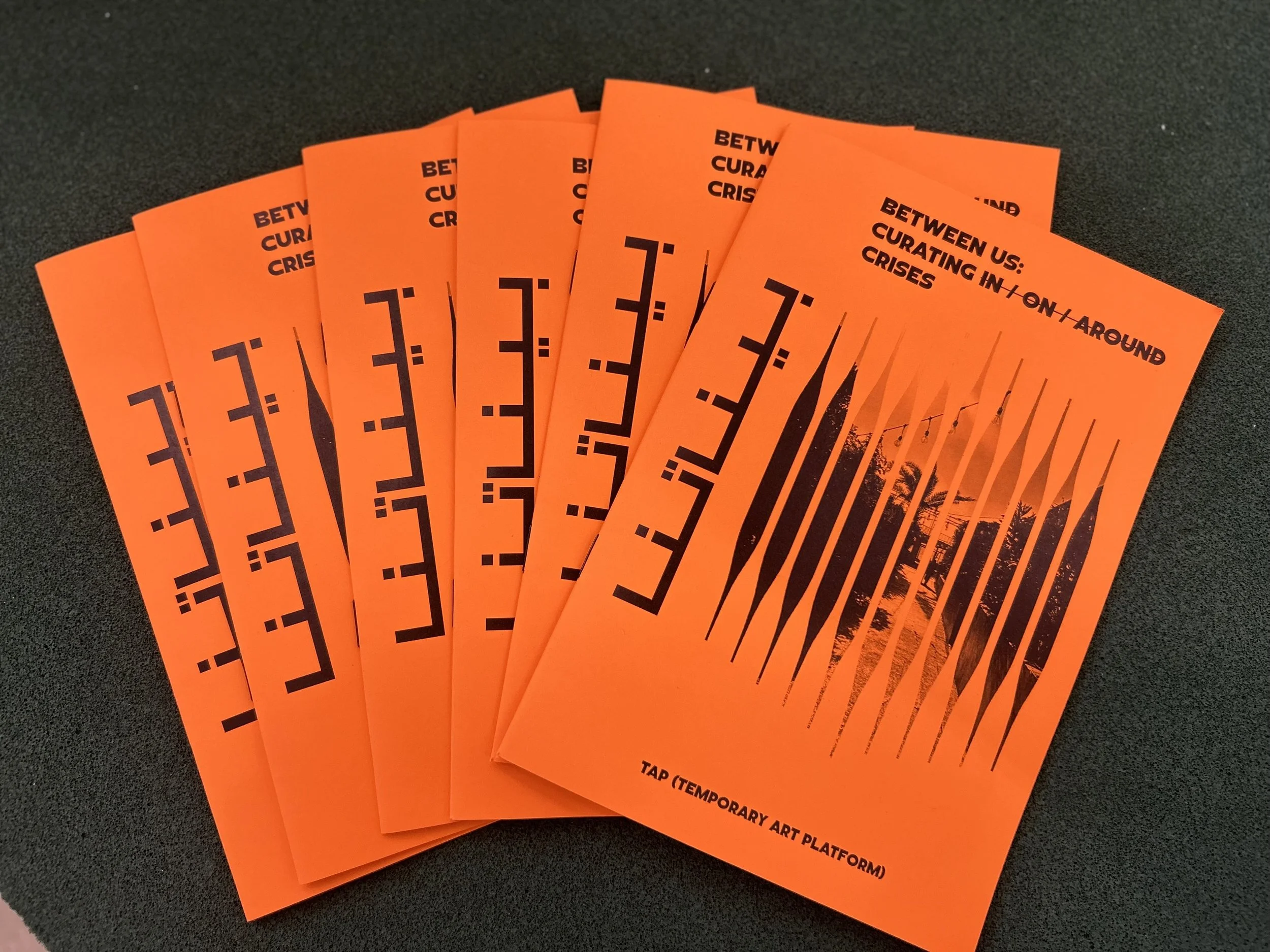

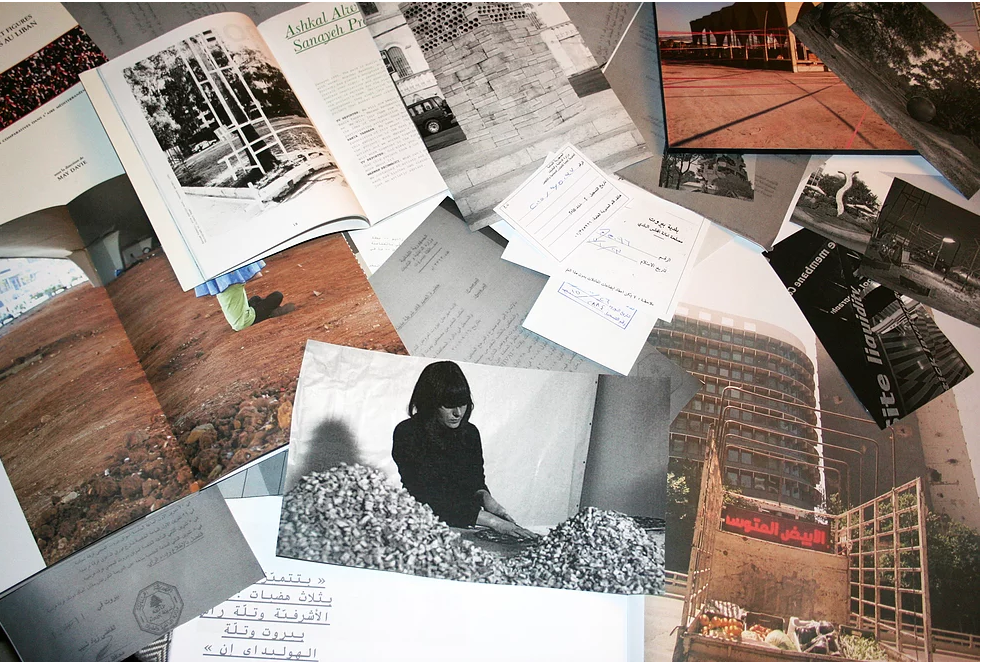

Between Us: Curating in / on / around crises

2025 | Lebanon

Scratch the surface, touch the sun

2022 | Lebanon

Of Water and Stone

2025 | Lebanon

What we make with what we have

2025 | Scotland

In the blink of an eye

2024 | Lebanon

The Database of Public Art Practices in Lebanon

2021 - ongoing | Lebanon

Impressions of Paradise

2025 | Lebanon